Citizenship and Civic Life

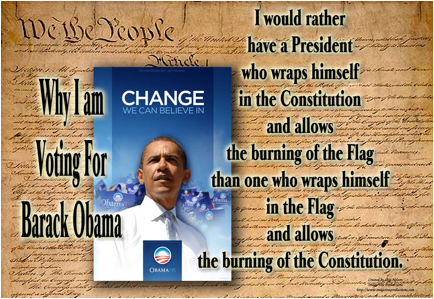

The Constitution:

Its Role in Public Debate

Based on Louis Michael Siedman, “Let’s Give Up on the

Constitution,” NYT, December 30, 2012.

Seidman is a professor of Constitutional Law at Georgetown

University and author of forthcoming book, On

Constitutional Disobedience

What

is Seidman’s thesis?

That

invoking the Constitution stops public/political debate about issues that need addressing

Frames

them as “constitutional questions” or limits, no-gos,

the impossible

Preventing

us from having real discussions about how we can solve contemporary problems

with the spirit of the constitution, i.e, our constitutional tradition as a whole as

our guide

Difference

between constitutionalism, following political traditions and using the

Constitution as a club to beat your political opponents into submission

Seidman traces our political history, the numerous uses of “unconstitutionalism”

Argues

that the progress of our country has often depended on overtly, explicitly

going against the Constitution

e.g.

drafting the Constitution itself, John Adams supporting the Alien and Sedition

Acts, TJ’s Louisiana Purchase, the drafting of the Civil War amendments without

the participation of Southern states, FDR pursuing the New Deal and threatening

the Supreme Court

Dissenting

justices often assert that their colleagues have ignored the Constitution, in

landmark cases, e.g. Miranda, Roe v. Wade, Bush v. Gore

“should give us pause” – how? Why? What are we to make of this?

Note:

He argues both interpretive methods

“originalism” and “living

constitutionalism”

cannot be reconciled;

some cases are decided invoking one method, others the other

Thus

we have no SINGLE tradition of interpreting the constitution

Or

rather that IS our tradition – of using it literally at times,

extrapolating at others

He

says, we shouldn’t chuck our traditions but rather follow them out of respect

rather than obligation

He’s

not advocating redesign of institutional design (“some matters are better left

settled”)

“What would change is not

the existence of these institutions, but the basis on which they claim legitimacy.

The president would have to

justify military action against Iran solely on the merits, without shutting

down the debate with a claim of unchallengeable constitutional power as

commander in chief.

Congress might well retain

the power of the purse, but this power would have to be defended on

contemporary policy grounds, not abstruse constitutional doctrine.

The Supreme Court could stop

pretending that its decisions protecting same-sex intimacy or limiting

affirmative action were rooted in constitutional text.”

“What has preserved our

political stability is not a poetic piece of parchment, but entrenched

institutions and habits of thought, and, most important, the sense that we are

one nation and must work out our differences.”

“If we acknowledged what

should be obvious – that much constitutional language is broad enough to

encompass an almost infinitely wide range of positions – we might have a

very different attitude about the obligation to obey. It would become apparent that people who

disagree with us about the Constitution are not violating a sacred text or our

core commitments. Instead, we are

invoking a common vocabulary to express aspirations that, at the broadest

level, everyone can embrace.

…If we are not to abandon

constitutionalism entirely, then we might at least understand it as a place for discussion, a demand that

we make a good-faith effort to understand the views of others, rather than as a tool to force others to

give up their moral and political judgments.”

“If even this change is

impossible, perhaps the dream of a country ruled by “We the people” is

impossibly utopian. If so, we have

to give up on the claim that we are a self-governing people who can settle our

disagreements through mature and tolerant debate. But before abandoning our heritage of

self-government, we ought to try extricating ourselves from constitutional

bondage so that we can give real freedom a chance.”