Lecture 13. Molecular strucure and polarity

Thursday 29 February 2024

VSEPR theory: The five basic shapes. VSEPR theory: The effect of lone pairs. VSEPR theory: Predicting nolecular geometries. Molecular shape and polarity.

Reading: Tro NJ. Chemistry: Structure and Properties (3rd ed.) - Ch.5, §5.9-5.10 (pp.242-250).

Summary

Lewis structures do not by themselves give us the ability to predict three-dimensional structure of the bonded atoms in molecules and polyatomic ions. But with the help of an additional interpretive tool, called valence shell electron pair repulsion (VSEPR), specific inferences of the likely geometric shapes can be made based on Lewis structures.

For a good website for viewing molecular structures, try ChemEd Digital Library Models 360.

Molecular structure: The five basic shapes

Once we are able to draw valid Lewis structures for simple molecules, we can use them to predict the shape of the molecule, or its three-dimensional structure. To do this, we apply the valence shell electron pair repulsion or VSEPR model.

It is convenient to define the steric number (abbreviated SN) for the central atom of a molecular structure. This amounts simply to a count of the number of bonded atoms plus the number of lone pairs present on the central atom. Tro's text refers to this count, what we are calling steric number, as the "number of electron groups". Since we end up counting a peripherally bonded atom only once, even if it is double- or triple-bonded to the central atom, we sometimes use the term electron domain (Tro's "electron groups") instead of electron pair in determining a value for SN. The value we assign to SN is the same as the number of electron domains (electron groups).

Note that any atom obeying the octet rule will not have SN > 4. This will be a very common situation, and we'll begin by analyzing the possible molecular shapes for steric number equal to 2, 3 and 4.

Linear geometry (SN = 2)

Examples of linear geometry (SN = 2)are provided by beryllium dichloride (BeCl2) and carbon dioxide (CO2). Note that the single bonds in the former and the double bonds in the latter both count the same in determining the steric number SN (i.e. number of electron groups) of the central atom. That is, in each case they count as one electron group, and therefore both molecules have SN = 2. The VSEPR model predicts a linear geometry and a bond angle of 180°.

Trigonal planar geometry (SN = 3)

Examples of trigonal planar geometry (SN = 3) are provided by boron trichloride (BCl3), the organic molecule formaldehyde (CH2O), and carbonate anion (CO32−). The VSEPR model predicts a trigonal planar geometry, with electron groups oriented toward the corners of an equilateral triangle. For the case in which all electron groups are bonding groups (as are all the examples mentioned above) this results in an ideal bond angle of 120°.

Tetrahedral-based structures (SN = 4)

If the SN = 4, the observed structures are based on the tetrahedron. For the case with all four electron domains bonding (then there are four atoms bonded to the central atom), the positions of the bound atoms lie at the corners of a tetrahedron. The ideal bond angles for this geometry are 109.5°.

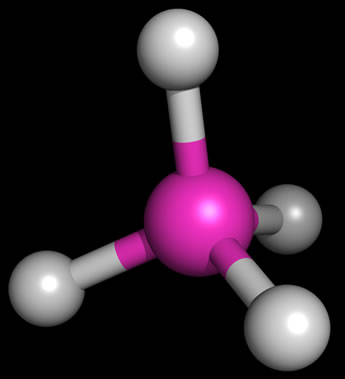

As an example of the tetrahedral structure,the figure at left shows the bond geometry of methane (CH4). Representing three-dimensional molecules on a two-dimensional page requires a bit of artistic skill. Below, examples of sketches of the three types of molecular structure that are based on a tetrahedral arrangement of electron domains around a central atom are shown. The sketches include the lone pairs (shown as balloons attached to the central atom). Solid wedges are meant to suggest bonds pointed out of the plane of the page, and dashed wedges suggest bonds that project behind the plane of the figure.

The bond angles for methane are indeed 109.5° - this is the angle made by any two C-H bonds (look at H at 12 o'clock and 8 o'clock - these are the bonds in the plane of the figure above). This ideal tetrahedral angle will hold when four atoms of the same type are bonded to the central carbon atom, but when we replace one of the bonding electron pairs with a nonbonding lone pair, the bond angles for the remaining bonds tend to shrink from the ideal value. The rationale behind this is that the negative charge of the lone pair is more spread out in space, and tends to repel the bonding pairs (which are more localized, being more constrained to the region between the two bonded atoms), thereby pushing them to be closer together in space. We see this effect when we move from methane (four bonding pairs, zero lone pairs; bond angles 109.5°) to ammonia (three bonding pairs, one lone pair; bond angles 107.3°) to water (two bonding pairs, two lone pairs; bond angle 104.5°). These molecules are illustrated in the sketch above, right.

Another feature the sketch aims to highlight is the distinction between what we can call the electron domain geometry and molecular shape. The underlying electron domain geometry is tetrahedral, since in each case we deal with four total electron domains (Reminder: The number of electron domains for a central atom is the same as its SN or steric number and is always the number of bonded atoms plus lone pairs). However, the molecular shape is what we see when we look just at atoms and ignore lone pairs. The molecular shape of methane is tetrahedral, the same as the underlying electron domain geometry, since each electron domain around the central carbon atom in methane corresponds to a bonded hydrogen atom. The molecular shape of ammonia appears to be a trigonal pyramid (a pyramid with a triangular base), since that is what is left when we take away one of the vertices of the tetrahedron and look at the shape formed by just the four atoms in the NH3 molecule. The water molecule has just three atoms, and (discounting the possibility of a three-membered ring) there are only two possible molecular shapes - linear, in which the three atoms lie along a straight line, with a bond angle of 180° - or, the atoms do not line along a single line and the molecular shape is "angular" or bent, with a bond angle of <180°. Since the underlying electron domain geometry of the water molecule is tetrahedral, we expect the bond angle to be near 109.5°. The somewhat smaller angle actually observed is attributable - as described above - to the repulsive effects of the lone pairs on the central oxygen atom.

Trigonal bipyramidal (SN = 5) and octahedral (SN = 6) structures

If the SN = 5, the observed structures are based on the trigonal bipyramid. For the case with all five electron domains bonding (then there are five atoms bonded to the central atom), the positions of the bound atoms lie at the corners of a trigonal bipyramid.

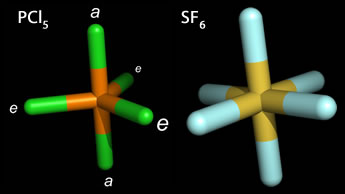

Phosphorous pentachloride (PCl5) provides an example of the trigonal bipyramidal structure, which is unique in that the peripheral posirtions are not all equivalent. Instead there are two distinct types of peripheral positions - axial (labeled a) and equatorial (labeled e). The bond angle between equatorial atoms is 120°, whereas the bond angle axial and equatorial atoms is 90°. With the substitution of a lone pair for a bonded peripheral atom, the VSEPR principle would predict an equatorially positioned lone pair to be more stable. When one lone pair occupies an equatorial position, and there are four bonded atoms, the molecular geometry is "see-saw".

Octahedral geometry results in the SN = 6 case, and all six positions are equivalent, located at the corners of a regular octahedron. An example of octahedral geometry is sulfur hexafluoride (SF6), in which all electron domains are bonding domains. Bromine pentafluoride (BrF5), and xenon tetrafluoride (XeF4) provide examples of the differing molecular shapes arising from octahedral electron domain geometry when one or two bonding domains, respectively, are replaced by lone pairs.

Predicting molecular geometries

The procedure for predicting molecular geometry from a molecular formula consisits of first drawing a valid Lewis structure for the molecule, from which a count of the nonbonding and bonding electron groups (also called electron domains) is obtained. The sum of these then gives the SN value for the central atom. Using this information, the molecular shape can then be predictted by VSEPR. All possible results of this analysis is presented in the table below.

Table 1: Molecular geometry summary

Steric number (SN) |

Ideal bond angle and orbital hybridization† |

Electron domain distribution | Shapes | |||

| 2 - linear | 180°, sp | 2 bonding, 0 nonbonding pairs | linear | |||

| 3 - triangular | 120°, sp2 | 3 bonding, 0 nonbonding pairs | trigonal planar | |||

| 2 bonding, 1 nonbonding pair | bent, angular | |||||

| 4 - tetrahedral | 109.5°, sp3 | 4 bonding, 0 nonbonding pairs | tetrahedral | |||

| 3 bonding, 1 nonbonding pair | trigonal pyramidal | |||||

| 2 bonding, 2 nonbonding pairs | bent, angular | |||||

| 5 - trigonal bipyramidal | 90°, 120° | 5 bonding, 0 nonbonding pairs | trigonal bipyramidal | |||

| 4 bonding, 1 nonbonding pair | see-saw | |||||

| 3 bonding, 2 nonbonding pairs | T-shape | |||||

| 2 bonding, 3 nonbonding pairs | linear | |||||

| 6 - octahedral | 90° | 6 bonding, 0 nonbonding pairs | octahedral | |||

| 5 bonding, 1 nonbonding pair | square pyramidal | |||||

| 4 bonding, 2 nonbonding pairs | square planar | |||||

| † The orbital hybridization is the combination of the atomic orbitals of the central atom required for the electron domain geometry. If you are not yet familiar with atomic orbitals or the concept of hybrid orbitals, just think of this column as containing another label to associate with SN and underlying geometry for now. | ||||||

Molecular geometry and polarity

Once we have a proposed molecular structure, we can use it to predict whether the molecule has a net dipole moment. The most important factors are the following: (1) The structural symmetry (or lack of it). (2) Differences in electronegativity in the pair of bonded atoms results in a bond dipole. The bonds in a structure must be checked for the presence or absence of a strong bond dipole. (3) It is most helpful to treat the bond dipoles as vectors, and learn to sum the bond dipole vectors to predict the net dipole moment of the molecule. It is often the case that the bond dipoles cancel due to the symmetry of the molecule. A striking example of this is carbon dioxide, in which the strongly polar C=O bonds give rise to two bond dipole moment vectors that are equal in magnitude (length), but are oriented in opposite directions. They therefore cancel (they sum to zero) due to the linear geometry of CO2, yielding a 180° bond angle.